-

OnkọweAwọn ifiweranṣẹ

-

-

Ẹrú, tabi

Ti di ẹrú.

Onisowo, tabi

Ẹgàn.

Awọn eniyan mimọ, tabi

Elese.

Introduction & Timeline:

Contrary to Eurocentrism’s pseudohistorical underpinnings, Afirika atijọ ko yasọtọ si aye atijọ.

For centuries, Eurocentric narratives have dominated global historiography, frequently marginalizing Africa’s role in world history. Perpetuated by colonial-era historians, these perspectives often depicted Africa as a dark, passive and isolated continent.

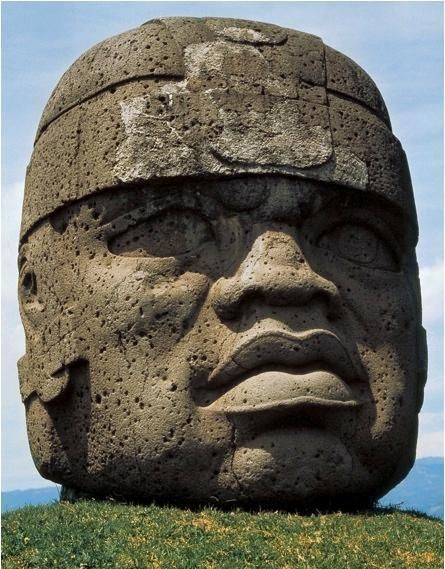

Historical and archaeological research across academia, reveals however an intricate picture of the ancient trans-saharan African trade, dating from approximately 5000 B.C (gun ṣaaju si awọn 1st orundun CE; and described as beginning with the age of African metallurgy in the case of the blacksmith-kings of Tarkur ‘old Senegal’), leta ti atijọ Ijọba ti Kuṣi ninu Kerma, Sudan; nipasẹ awọn Darb el-Arbain trade route, and facilitating the exchange of diverse commerce in incense, wheat, spices, gold, salt, animals/poultry, skilled artisan’s and ivory; and importantly, the import of minerals such as ‘obsidian'lati Tarkur [old Senegal] to create blades, objects, and metalworking – underscoring the high value placed on African trade-craft within these trade corridors. The region was an ethnic melting pot, with commerce spanning extensive geographical footprints; with records showing lasting contributions of Africa to other regions and cultures, across Mesopotamia, the Levant, ati awọn Aegean world, and anthropological research recently discovering colossal Olmec sculptures with African facial lips and nose features, and Manding inscriptions ninu awọn ipon igbo ti South America, suggesting early trans-continental connections, and cultural exchanges.

Awọn ọna Silk:

Iṣowo gbe alaye, ati awọn nẹtiwọọki iṣowo isomọ pọ Afirika to most of the old world, brought about an exchange of trade in oriental [eastern] silks for awọ yẹlo to ṣokunkun, jade, àwọ̀, turari, wura, epo, Awọn ohun elo ti a ṣe, pẹlu mythical eda bi awọn giraffe [tabi, awọn qilin, revered ni Kannada, Japanese ati Korean itan ayeraye] ati be be lo, sunmọ 114 Bc, lati awọn jù Oba Han.

Awọn aworan ti siliki gbóògì wà ohun iyasoto Kannada export during this period, and the Han imperial documents show diplomatic and trade relations between the Han Oba and Africa, with a diplomatic envoy ‘Zhang Qian' ti a firanṣẹ si iṣowo transcontinental ti o ni aabo, bakannaa ṣẹda awọn aabo aabo iṣelu, fun iṣowo siliki ti n dagba. Iwa yii tẹsiwaju si ibẹrẹ Oba Mingpẹlu awọn igbasilẹ ti 'Zheng He' (Olukọni diplomat ati Admiral) ṣabẹwo si inu ilohunsoke ti Afirika laarin Ọdun 1419 CE ati Ọdun 1433 CE, ati awọn aṣoju Afirika / awọn aṣoju ti a pe nipasẹ Emperor Zhu Di lati ṣe ayẹyẹ pupọ Chinese odun titun ni awọn rinle ti won ko Ilu Eewọ; sunmọ Ọdun 1421 CE.

Awọn Graeco-Roman periplus "Periplus ti Okun Erythraean” tun pese igbasilẹ ti awọn itineraries ti ọkọ oju omi ati awọn aye iṣowo laarin Afirika ati awọn ebute iṣowo ita / ilana ilana.

Awọn Ijọba Romu jogun awọn nẹtiwọki iṣowo ti iṣeto ti o ṣẹda apakan ti Silk Road laarin awọn ọna iṣowo ila-oorun ati Afirika, awọn wọnyi iṣẹgun ti Egipti ninu 30 Bc.

Lucius Septimius Severus’s Ancestry – (“Aethiops quidam e Numero Militari”):

Ijọba Romu ti o gbooro gba iṣowo, aristocracy ati awọn aṣa ologun ti awọn alaṣẹ ijọba ti awọn ipinlẹ ọba-aṣẹgun, ti iṣeto awọn ibatan ile-igbimọ / ile-ẹkọ giga. Iyatọ-ẹya pupọ ti o tobi pupọ ti o wa laarin awọn olugbe ti o nwaye ti Ilẹ-ọba Roman Roman ti Ariwa Afirika jẹ akojọ si ni Notitia Dignitatum (“Atokọ Awọn Ọfiisi Roman Isakoso”), ati bi o ti ṣe afihan ninu ọmọ Afirika ti oye (Aethiopes/Mauri/Moorish) ologun rejimenti lara awọn Roman Army Germania, ati Britannia ipolongo, ati ni Lucius Septimius Severus’s baba-nla.

Ninu Ọdun 193 CE, Lucius Septimius Severus ti a ade olori ti gbogbo awọn Ijọba Romu o si di Rome ká akọkọ Afirika Emperor; a product of the cultural and political union/alliance between an African father, and a mother of Roman descent, coming from a prominent Roman family of equestrian rank.

Awọn julọ ohun akiyesi nigbamii irin ajo ti Emperor Septimius Severus ká Nupojipetọ-yinyin tin to agbegbe Lomu tọn mẹ Britannia; ati nibiti o ti ku si York, sunmọ Ọdun 211 CE.

During this period African’s were known by many names, and led the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula circa Ọdun 711 CE titi Ọdun 1492 CE, awọn wọnyi ni isubu ti awọn Roman Dioecesis Africae (Roman Diocese of Africa), and the Roman Empire.

Iṣowo siliki ni Afirika tẹsiwaju fun igba pipẹ, ati pe ohun ti a mọ ni bayi bi 'awọn ipa-ọna siliki, tabi ọna siliki' wa fun diẹ sii ju ọdun 1,500, titi di isunmọ. Ọdun 1453 CE.

Awọn Zimbabwe nla, Ara Malia ati Ottoman Ghana lay on the trade routes, between the east coast and the interior of Africa, giving rise to a host of middlemen and trading posts, with the requirement for taxes and protection along the way.

Ẹsin, awọn imọ-ẹrọ tuntun, ĭdàsĭlẹ ati awọn imọran tan kaakiri awọn ọna iṣowo Afirika gẹgẹ bi omi ti n ṣafẹri bi awọn ẹru, ti o yorisi idagbasoke ti awọn ilu aṣa ni inu inu ti awọn ọna iṣowo trans-saharan, eyun Gao ati Timbuktu, ati be be lo

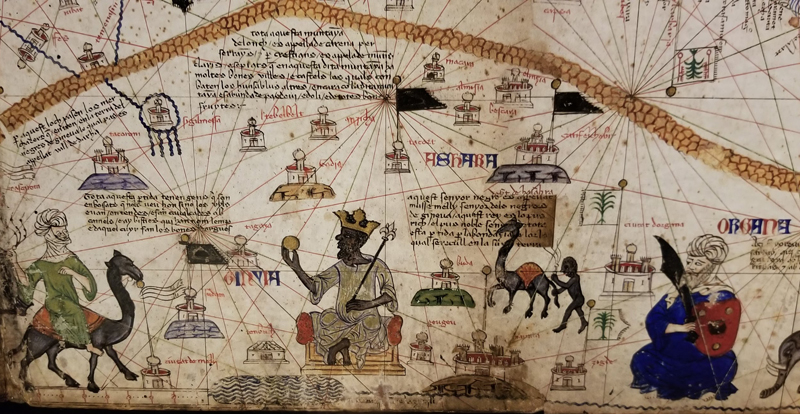

Ni tente oke ti awọn African Renesansi, the well organised system of government under the leadership of King’s and Queens’s, such as Shanakdakhete (1st century BCE onwards Kingdom of Kush (Nubia, modern-day Sudan); Kaleb of Axum (6th century CE onwards); Tunka Manin (11th century CE onwards, Region of Ghana Empire (Modern-day Mali, Mauritania, Senegal); Sundiata Keita (1217–1255 CE) Region of Mali Empire (Modern-day Mali and surrounding regions); Musa Keita I tabi Mansa Musa (C.1312–1337 CE), the extensive travel and trading networks of African merchants and African scholars developed an important book trade, establishing The Kingdom of Kush, as well Timbuktu (Modern-day Mali) as scholarly centres in Africa [known for producing the Meroitic script, one of Africa’s earliest writing systems,] circa 4th CE ati siwaju.

As a result, tales of Africa’s wealth, exotic exports, renaissance, lifestyle and high-culture fuelled speculation in Yuroopu, as not just being extremely rich, but also being particularly mysterious. These stories helped prompt the European interest and exploration of opportunities in Africa.

The decline of these African city-states resulted from a shift in the dynamics of international trade, internal rivalries [notably, the Saadian/Ilu Morocco ayabo ti awọn Niger inu ilohunsoke, Ogun ti Tondibi, ati Ogun ti Alcácer Quibir] titun gbokun isowo ipa-, to ti ni ilọsiwaju Maritaimu / lilọ ogbon ati ohun ija, pọ eletan ati idije fun ilẹ, wiwọle si de ati oro bi goolu, a naficula ni lagbaye gaba ati alagbaro.

Pipin iṣelu ti agbegbe naa, jija ti awọn ilu aṣa-ọpọlọpọ, awọn iwe-iwe ati awọn iṣura ti awọn ijọba ti aarin gẹgẹbi Mali, Songhai, Kongo/Congo, ati wiwa ti n pọ si ti Ottoman‘s, and Portugal, marked the end of the region as a dynamic force in commerce.

The beginnings of European

Activity in Africa:

Gẹgẹbi awọn aririn ajo ajeji miiran ati awọn onisọ ọja ṣaaju, awọn oniṣowo ati awọn oniṣowo ile Afirika ni esan ṣii si awọn tuntun ti Ilu Yuroopu.

Awọn dide ti akọkọ European onisowo, lori 5440 ọdun lẹhin ti awọn paṣipaarọ ti (mọ ati ki o ni akọsilẹ) iṣowo bẹrẹ ni Afirika, o le sopọ mọ ọdọ olorin Portuguese kan 'Antam Gonçalvez' ẹniti, lẹhin ti o gbọ awọn itan ti agbara fun iṣowo ati ere, bẹrẹ irin ajo lọ si Iha Iwọ-oorun Iwọ-oorun Iwọ-oorun Afirika ni Ọdun 1441 CElabẹ itọnisọna ti 'Dom Henrique of Portugal, Duke of Viseu’ to obtain seal skins, spices and oil, for onward sale in Lisbon.

Portugal was desirous to retain a monopoly on trade in Africa, and sought justification of its position, ‘early discoveries’ and sphere of influence (awọn titun-ri iṣowo ipa-), nipasẹ a Papal Bull ti Ọdun 1442 CE, ti a yàn nipa Pope Eugene IV, the consequence of which would be the legitimisation of the capture and enslavement of non-Christian Africans [in the newly explored land], under the premise and designation of the enterprise as a crusade; a Papal Bull nipasẹ Pope Nicolas V, ni 1452 CE ati 1455 SK, ati Papal akọ màlúù kan di mímọ awọn Adehun ti Tordesillas (ni ọdun 1494 SK).

Ni akoko, nigba awọn 15th ati 17th sehin, fadaka ati wura wà ni agbaye awọn ajohunše ti paṣipaarọ ni Europe ati Asia. Ipese awọn irin iyebiye jẹ pataki lati ṣe igbelaruge awọn ọrọ-aje, ati lati ṣe afẹyinti awọn owo nina fun paṣipaarọ ati gbigbe wọle.

Kanna kannaa ati ohun elo ologun wà operational ni nilokulo ti Mayan wura nipa Spain, ati nigbati yi je ti re, awọn exploits ti fadaka maini ti Mexico. Nitootọ, pupọ ninu idije laarin awọn orilẹ-ede Yuroopu ni awọn ọrundun 15th ati 18th ni a bi lati inu ifẹ lati daabobo ati lati ṣe atilẹyin awọn ọrọ-aje ati awọn owo nina wọn.

Awọn iroyin ti awọn ilokulo Portuguese ni Afirika ni a gbọ ni adugbo Spain, ati ki o kọja awọn iyokù ti Yuroopu, pẹlu julọ inú sosi jade ti awọn ikogun.

Laarin Ọdun 1495 CE ati Ọdun 1559 CE, ọgọ́rọ̀ọ̀rún àwọn ọkọ̀ ojú omi Potogí ni àwọn ọmọ ilẹ̀ Gẹ̀ẹ́sì kó, tí wọ́n kó wọn, tí wọ́n sì kó wọn lọ, bákan náà, àwọn ará Gẹ̀ẹ́sì ń kópa nínú iṣẹ́ agbófinró. Ogun ti Agadir ('Santa Cruz') Ọdun 1541 CE.

Ọba John III ti Portugal kowe si Queen Mary of England (Ọdun 1555. CE) Bi abajade, awọn atunṣe ti o beere fun awọn ọkọ oju omi ti o gba ati ti a ji. Ni pataki, ni Ilu Pọtugali, Spain ati kọja Yuroopu, ọba ni o ṣe agbekalẹ awọn akọle fun awọn monopolies iṣowo kọja 'aala iṣowo ti n yọ jade' tuntun, ti n gba iṣẹ kan, tabi owo-ori fun awọn monopolies iṣowo.

Notable timelines of European involvement in Africa include Spain (from 1462); Great Britain (lati 1562, with Queen Elizabeth I granting legitimacy to the privateering activities of John Hawkins, Francis Drake, et al. nipasẹ awọn osise ipinfunni ti a oto ndan ti apá, ati Bermuda di ohun-ini ade ni ọjọ 23 Oṣu kọkanla 1614); Holland (lati 1592); France (lati 1594), ati be be lo.

Iṣowo pẹlu Afirika nilo ọrọ nla, ati inawo. Ó jẹ́ àǹfààní àkànṣe ti àwọn ọba ilẹ̀ Yúróòpù, àwọn ọlọ́lá, tàbí àwọn oníṣòwò ọlọ́rọ̀. Awọn ara ilu Yuroopu ni idagbasoke awọn ilọsiwaju siwaju sii, fun iṣowo ti o ṣojukokoro ni Afirika, nipasẹ idasile awọn ile-iṣẹ iṣowo. Ile-iṣẹ Dutch East India, Ile-iṣẹ Danish West India Company ati Ile-iṣẹ Faranse Iwọ-oorun India ni a ṣẹda ni 1602/1659/1664 ni atele, eyiti o jẹ ki ọpọlọpọ awọn oniṣowo lọpọlọpọ lati ṣe idoko-owo ni ere tuntun ti a rii ni Afirika; iṣeduro, ati itankale awọn ewu iṣowo rẹ.

Awọn Ile-iṣẹ ti Royal Adventurers ti England ti a da ni 1660 nipa Ọba Charles II ti England, iwe-aṣẹ ti o funni ni anikanjọpọn ti iṣowo ni etikun iwọ-oorun ti Afirika, ti n yipada sinu Ile-iṣẹ Royal African ninu 1672.

Itankalẹ ti ile-ẹkọ imotuntun yii, apapọ ọja iṣura / ile-iṣẹ iṣowo, jẹ idagbasoke pataki julọ julọ ni agbaye ti 17. orundun commerce. This guaranteed Yuroopu could harness its resources towards the structuring and maintaining of trade in Africa, as well as much of the world.

Nikẹhin, o ṣeto iṣeto nipasẹ eyiti Yuroopu, lairotẹlẹ, tan, infiltrated ati colonized julọ ti aye.

Lakoko yii ala-ilẹ awujọ ati iṣelu ti Yuroopu ni iriri awọn iyipada ti o tẹle lati feudal, si ọjà ati si ibudo iṣowo ile-iṣẹ kan. Lọndọnu, Antwerp, Liverpool, Amsterdam ati Nantes farahan bi awọn ile-iṣẹ inawo akọkọ ti Yuroopu.

Reductionism and the

tradition of diminishing

African cultures and its

place in history: [The

Language of Legal

Fiction.]

Awọn Corpus Juris [The body of Laws] creates a critical foundation from which to think about the problem of legal personhood.

Ise adayeba / lex naturalis [Natural Laws], (eternal and immutable) renders conceptually, corporeal values, intrinsic to human nature; complex sentient creatures imbued with, not only individualism, needs and appetites, but self-awareness (consciousness), rights, privileges, obligations, the capacity to create legal relations, and by the limits of pain, illness, suffering and death.

Awọn imọran iwuwasi ilana ilana ti jurisprudence (awọn ofin ofin) ṣẹda awọn oju-ọna ti idanimọ fun ọpọlọpọ / awọn nkan lọpọlọpọ, awọn ẹgbẹ, awọn ẹni-kọọkan, ilana ti “miiran”, humanizing, and expanding the community of persons. This is problematic, plagued by uncertainty and indeterminacy (at worst, arbitrary), and limits the full potential and promise of personhood.

Oblivious to the significance of the word, the pervasive use of terms such as “slave” and/or words analogous to this, pervades and conditions all other inherent identities, either chosen or given. To reduce the person [or body] to a non-human noun is to produce linguistic violence, and strips the individual of agency. To argue contrary flies in the face of empirical fact. The scholarly exercise of embellishing and sugar-coating the language of historical recall, implies a degree of wilful and/or premeditated amnesia and wastes an opportunity to reinforce the brutish-callousness of the word.

Likewise, the reduction of Afirika realities as mythic representations, or phenomena, devoid of history, commerce, philosophy and intellectual pursuits – that Africa had no history – is a Eurocentric idea, given the aforementioned timeline, and perpetuates a narrative that erases the tangible contributions of African city-states to global civilization. So also is the contemporary construct of ‘third-world’, ‘underdeveloped’, ‘developing’, or ‘undemocratic’ – judged pursuant to Eurocentric standards.

Notably, distinguished African historian’s, anthropologist’s and sociologist’s such as Cheikh Anta Diop, John Henrik Clarke, ati WEB Du Bois et-al, have defined this peculiar/Eurocentric faux-ethnographic characterisation of the African sociocultural ethnology, as indeed a ‘new invention’, a ‘religion [or idea]’ founded on the Eurocentric (scholarly) dogma that all the hues of God are grounded on the intrinsic hierarchy of religious orthodoxy; with the inevitable corollary of the collective physical, ideological, religious, systemic or cultural traits of the ‘Other’ (individuals who were outside the contemporary hegemonic power structure) as significantly less prized by ‘modern societies’.

The primary basis for this reconfiguration was to institute, and strengthen the agency of Eurocentric capitalist systems, backed by a cluster of social, incorporeal/religious, semantic conjecture and legal regimes.

Bi abajade, ati laisi iyemeji eyikeyi, nibiti ẹsin tuntun yii (tabi itumọ hegemonic) ko ni anfani lati ṣẹgun awọn iyipada nipasẹ itusilẹ alaafia tabi iberu, o gbe awọn ọna atijo / aiṣedeede lati daabobo agbara rẹ, awọn ofin ikọsilẹ, aṣa ati awọn ile-iṣẹ lati fi sinu ipa awọn oniwe-anfani.

Ipari:

A sosioloji ti gaba emerged nipasẹ awọn Papal Bulls ti Ọdun 1442 CE, Ọdun 1452 CE, Ọdun 1455 CE, ati Ọdun 1494 CE. Its associated theories and pseudo-scientific markers of ‘natural differences’ of awọn 18th, the 19th, ati the 20th orundun, institutionalised and provided a moral justification to sustain the systemic avarice emanating from Europe, ati America; leading up to the 21st century. The core of this system is normalised through contemporary forms and mediums; vastly embedded in the social, scientific, economic/financial, political (public policy), academic, spiritual, media, literary and cultural spaces, and exercised through an intricate web of norms and laws, the institutional and structural power accumulated recently.

Awọn European intervention sunmọ mid-15th century, wó lulẹ African to ti ni ilọsiwaju, onitẹsiwaju, oselu ati awujo ẹya. Titi di aarin ọdun karundinlogun (CE), Afirika je ohun nyoju aje powerhouse. Àárín Gbùngbùn Áfíríkà ní àṣà ìbílẹ̀ irin tí ó gbóná ti tó wà ní ìsopọ̀ pẹ̀lú Àríwá, Gúúsù àti Òkun Íńdíà. Iwọ-oorun Afirika ni asopọ si Mẹditarenia nipasẹ awọn ọna iṣowo kọja Sahara. The European dide ti Ọdun 1441 CE siwaju, Idilọwọ awọn adayeba itankalẹ ti awọn burgeoning African intricate àsà ti owo ayika; awọn oniwe-ise, specialized / ijinle sayensi, atijọ ti esin ati omowe ala-ilẹ.

Idarudapọ ti o tẹle ni o fa iyapa ti awọn idile, ti ko ni ibanujẹ ailopin lori ọkunrin, obinrin ati awọn ọmọde, with Africa losing centuries-old skilled artisans, goldsmiths, jewellers, masons, carpenters, farmers, musicians, priests, kingmakers and scholars; the loss of neighbours, brother’s, sister’s, aunt’s, uncle’s, son’s, daughter’s, cousin’s, mother’s, father’s, and culture’s.

What is rarely told is that a staggering 40% of the UK’s budget in Ọdun 1833 CE, the equivalent of approximately £20bn in today’s terms, was used to compensate English merchants towards the eventual demise and collapse of the illicit profiteering of trade in Africa; while excluding displaced African’s from any restitution.

Fun arosọ kan ti o da lori ilana ti iṣelọpọ pseudo-hegemonic cum-capitalist, ipa apanirun lori kọnputa Afirika, ni idile idile, ọrọ-aje ati awọn ofin inawo, ko ni iwọn.

© ÀGBÁRA

Bibliography:

1. African Historical Reach and Bibliography:

- Fage, J. D., & Oliver, R. A. (Eds.). (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa: Volume 2, c. 500 BC–AD 1050. Cambridge University Press.

- This book provides an extensive overview of ancient Africa, detailing the role of trade routes, metallurgy, and economic exchanges across the Sahara, which connects with the spread of African cultural practices.

- Ehret, Christopher. (2002). The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800. University of Virginia Press.

- Ehret’s work focuses on early African civilizations, including those involved in trans-Saharan trade, providing a basis for understanding the significance of metallurgy and commerce in pre-Islamic West Africa.

- McIntosh, Roderick J. (1998). The Peoples of the Middle Niger: The Island of Gold. Wiley-Blackwell.

- McIntosh’s research delves into the role of the Niger River in trade and the movement of goods across West Africa, including gold, salt, and other materials crucial to the trans-Saharan trade network.

- Dixon, David, and Dixon, Roger. (1983). “The Trans-Saharan Gold Trade: The Kingdom of Ghana and the Islamic Empires of the West.” History Today, 33(10), 16-23.

- This article covers the importance of the gold trade and its role in the ancient trans-Saharan trade network, with specific emphasis on the early West African empires like Ghana and their trading relationships.

- Rathbone, R. (2000). “The Trans-Saharan Trade.” In Africa: The Art of a Continent, edited by T. Phillips, 72-75. Royal Academy of Arts.

- Rathbone discusses trans-Saharan trade in terms of its artistic and cultural impacts, including how goods like ivory and gold affected the material culture of ancient African societies.

- Oviedo, Fernández de. (1535). Natural History of the West Indies (Translated by Sterling A. Stoudemire, 1959). University of North Carolina Press.

- Oviedo’s work, though initially focused on the Americas, is referenced in discussions about African influences in pre-Columbian American contexts, especially considering potential contacts suggested by more recent studies of inscriptions.

- Van Sertima, Ivan. (1976). They Came Before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America. Random House.

- Although this work has faced some scholarly criticism, it remains a widely cited source discussing the possibility of pre-Columbian African contact with the Americas, including evidence like inscriptions.

- Mauny, Raymond. (1971). “The Western Sudan.” In General History of Africa: Volume II, Ancient Civilizations of Africa, edited by G. Mokhtar, 290-314. Heinemann.

- This chapter in the UNESCO General History of Africa provides details on the historical and cultural dynamics of the Western Sudan, including trade routes, metallurgical practices, and commerce that spanned the Sahara.

9. Cheikh Anta Diop

- Diop, Cheikh Anta. (1981). Civilization or Barbarism: An Authentic Anthropology. Lawrence Hill Books.

- This foundational work examines African civilizations’ contributions to world history, including their advancements in metallurgy, trade, and cultural dissemination.

- Diop, Cheikh Anta. (1974). The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality. Lawrence Hill Books.

- A critical exploration of African civilizations’ roles in shaping the ancient world, focusing on Egypt and its connections to sub-Saharan Africa.

10. John Henrik Clarke

- Clarke, John Henrik. (1993). African People in World History. Black Classic Press.

- A concise yet impactful narrative of Africa’s role in global history, emphasizing its civilizations, trade routes, and the spread of knowledge.

- Clarke, John Henrik. (1994). Christopher Columbus and the African Holocaust: Slavery and the Rise of European Capitalism. A&B Books.

- This book critiques European expansionism, connecting the transatlantic slave trade to Africa’s economic exploitation.

11. Basil Davidson

- Davidson, Basil. (1994). Africa in History: Themes and Outlines. Simon & Schuster.

- While not African himself, Davidson’s collaborative work with African scholars has provided deep insights into the trans-Saharan trade and African empires.

12. Runoko Rashidi

- Rashidi, Runoko. (2001). Introduction to the Study of African Classical Civilizations. Karnak House.

- Focuses on ancient African civilizations’ global impact, including their trade networks and intellectual contributions.

- Rashidi, Runoko. (1995). African Presence in Early Asia. Transaction Publishers.

- Co-authored with Ivan Van Sertima, this work traces African influence in Asia, offering parallels to Africa’s role in ancient global trade.

13. Ivan Van Sertima

- Van Sertima, Ivan (Ed.). (1983). Black Women in Antiquity. Transaction Publishers.

- Highlights the contributions of African women in ancient trade, governance, and culture.

14. Molefi Kete Asante

- Asante, Molefi Kete. (2007). The History of Africa: The Quest for Eternal Harmony. Routledge.

- A detailed overview of Africa’s historical contributions, including its trade empires and intellectual traditions.

- Asante, Molefi Kete. (1988). Afrocentricity: The Theory of Social Change. African World Press.

- Introduces Afrocentric theory as a lens to understand Africa’s historical and cultural prominence in global history.

15. Sylviane A. Diouf

- Diouf, Sylviane A. (1998). Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. NYU Press.

- Explores the role of African Muslim scholars and merchants in shaping the Atlantic world through trade and culture.

16. George G.M. James

- James, George G.M. (1954). Stolen Legacy: Greek Philosophy is Stolen Egyptian Philosophy. Philosophical Library.

- In this seminal work, James argues that much of what is attributed to Greek philosophy is rooted in African (Egyptian) knowledge systems, highlighting Africa’s intellectual contributions to the world.

17. Chancellor Williams

- Williams, Chancellor. (1974). The Destruction of Black Civilization: Great Issues of a Race from 4500 B.C. to 2000 A.D. Third World Press.

- A groundbreaking study of African civilizations, detailing their decline due to internal and external factors, including European and Arab incursions, and emphasizing the centrality of trade in African history.

18. Yosef Ben-Jochannan

- Ben-Jochannan, Yosef. (1993). Africa: Mother of Western Civilization. Black Classic Press.

- A comprehensive examination of Africa’s foundational role in the development of Western civilization, including trade, science, and culture.

- Ben-Jochannan, Yosef. (1989). Black Man of the Nile and His Family. Afrikan World Infosystems.

- Explores the contributions of Nile Valley civilizations to global history, with a focus on the interconnectedness of African societies and trade networks.

19. Walter Rodney

-

- Rodney, Walter. (1972). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Howard University Press.

- Examines the economic and social impact of European intervention in Africa, particularly in disrupting preexisting trade networks.

- Rodney, Walter. (1981). A History of the Upper Guinea Coast, 1545 to 1800. Monthly Review Press.

- Focuses on African agency in trade and governance before and during European incursions.

- Rodney, Walter. (1972). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Howard University Press.

20. Vansina, Jan

-

- Vansina, Jan. Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990.

21. Wright, Donald

-

- Wright, Donald. The World and a Very Small Place in Africa. New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1997.

In-Text Citations

- For information on the ancient trans-Saharan trade, reference Fage & Oliver (1975) ati Ehret (2002), as both texts provide foundational insights into the role of trade across the Sahara from prehistoric times.

- Awọn McIntosh (1998) ati Dixon & Dixon (1983) references provide additional support for understanding the trade routes that facilitated exchanges of goods like gold and salt, critical to West Africa’s economy.

- Awọn Van Sertima (1976) ati Oviedo (1535) sources cover anthropological evidence of early African inscriptions and cultural influences potentially present in the Americas.

- For metallurgy in ancient Africa, Mauny (1971) ati Munson (1980) discuss the techniques and cultural significance of early metalworking, emphasizing its role in trade and economy across West Africa.

2. Africa/Chinese Historical Links and Bibliography:

- Liu, Xinru. (2010). The Silk Road in World History. Oxford University Press.

- This book offers an overview of the Silk Road, including the early Han Dynasty’s efforts to expand trade and diplomatic relations across Asia, reaching as far as the Middle East and Africa. It also discusses Zhang Qian’s missions and the Chinese silk monopoly.

- Adshead, S.A.M. (2000). China in World History. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Adshead’s work covers the history of China’s interactions with the world, detailing the Han Dynasty’s and Ming Dynasty’s diplomatic outreach to regions including Africa, as well as trade exchanges involving exotic goods.

- Levathes, Louise. (1994). When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433. Oxford University Press.

- Levathes provides an in-depth look at the maritime expeditions of Zheng He, including his journeys to East Africa, diplomatic exchanges, and the arrival of African emissaries in China during the Ming Dynasty.

- Hansen, Valerie. (2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press.

- Hansen explores the Silk Road from a fresh archaeological and historical perspective, touching on the trade goods (like silk, jade, and spices) that moved through interconnected trade routes. She also discusses cultural exchanges, including the reverence for exotic animals like the giraffe.

- Yao, Alice. (2010). “Silk Road Traders: A Global Business Network.” Journal of World History, 21(3), 255-274.

- Yao examines the Silk Road’s role as an intercontinental network for trade and culture, which allowed the movement of goods like amber, jade, and gold across Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

- Wang, Gungwu. (1998). The Nanhai Trade: A Study of the Early History of Chinese Trade in the South China Sea. Eastern Universities Press.

- This study focuses on Chinese maritime trade, particularly during the Han and Ming Dynasties, exploring early connections with Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, which facilitated exchanges with Africa.

- Needham, Joseph. (1971). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 4: Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge University Press.

- Needham’s work delves into Chinese nautical advancements that made expeditions to Africa possible, providing insights into Admiral Zheng He’s voyages and the types of goods and diplomatic missions exchanged.

- Blanchard, Ian. (2001). Mining, Metallurgy and Minting in the Middle Ages: Asiatic Supremacy, 425–1125. Franz Steiner Verlag.

- This book contextualizes the economic and technological exchange of tools, metalworking, and other commodities involved in trade between China and Africa and highlights the integration of such goods into local economies.

- McNeill, William H. (1991). The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community. University of Chicago Press.

- McNeill’s history provides a broader context for understanding intercontinental exchanges, including China’s influence on Africa and Europe through goods, cultural exchanges, and diplomatic relations.

- Dreyer, Edward L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. Pearson Longman.

- This book is an authoritative source on Zheng He’s voyages, detailing the scope of his expeditions and the diplomatic relationships established with East Africa, as well as the Chinese court’s welcoming of African envoys.

In-Text Citations

- For references on the early Chinese silk trade and Zhang Qian’s diplomatic missions under the Han Dynasty, use Liu (2010), Adshead (2000), ati Hansen (2012), all of which provide insight into the reach of the Silk Road and Chinese diplomatic expansion.

- For the significance of Zheng He’s voyages to Africa during the Ming Dynasty, Levathes (1994) ati Dreyer (2007) offer comprehensive details, including the exchange of envoys and rare African animals.

- On the broader context of intercontinental trade routes involving Africa, Yao (2010) ati Needham (1971) provide valuable insights into maritime technology and the kinds of exotic goods exchanged.

- Wang (1998) ati Blanchard (2001) can be cited for details on the types of goods involved in trade (amber, jade, silk, spices, and tools) and the technology enabling long-distance trade across the Indian Ocean.

3. African Expansion, Historical Influence and The Roman Empire Bibliography:

- Casson, Lionel. (1989). The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton University Press.

- Casson’s authoritative work on Periplus ti Okun Erythraean provides insight into Graeco-Roman maritime routes, trade opportunities, and African trade hubs in relation to Rome’s expanding influence in East Africa and the Indian Ocean.

- Ball, Warwick. (2016). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge.

- This book explores the Roman Empire’s eastern trade networks and its incorporation of foreign elites, military, and aristocratic structures into the Roman political fabric, highlighting the importance of African and Eastern influences.

- Birley, Anthony R. (1971). Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. Yale University Press.

- Birley’s biography details the life of Septimius Severus, his ancestry, rise to power, and military campaigns, particularly focusing on his African heritage and political alliances within the Roman Empire.

- Mattingly, David J. (1995). Tripolitania. University of Michigan Press.

- Mattingly’s work on Roman North Africa provides details on the Roman Diocese of Africa and African military regiments, such as the Moorish (Mauritanian) soldiers, and offers an analysis of the African provinces’ influence within the Roman administrative and military systems.

- Edmondson, Jonathan, & Keith, Alison. (Eds.). (2008). Romanization and the City: Creation, Transformations, and Failures. University of Toronto Press.

- This book explores how Roman cities, especially in North Africa, were shaped by Roman policies and by African influences, highlighting the roles of African elites and their integration into Roman aristocratic structures.

- Shaw, Brent D. (2014). Bringing in the Sheaves: Economy and Metaphor in the Roman World. University of Toronto Press.

- Shaw discusses the economic integration of African provinces into the Roman Empire, detailing trade, agriculture, and commerce, particularly after the Roman conquest of Egypt, and Africa’s role in the empire’s economy.

- MacDonald, Eve. (2015). Hannibal: A Hellenistic Life. Yale University Press.

- While primarily a biography of Hannibal, this book provides context on North Africa’s military traditions and the legacy that influenced later Roman-era African leaders and military regiments.

- Hoyos, Dexter. (2003). Hannibal’s Dynasty: Power and Politics in the Western Mediterranean, 247–183 BC. Routledge.

- Hoyos’s study of the Punic legacy offers insights into the military and political dynamics in North Africa that shaped the elite African regiments within the Roman army, which were later integral to campaigns in Germania and Britannia.

- Lewis, Archibald R., & Runyan, Timothy J. (1985). European Naval and Maritime History, 300–1500. Indiana University Press.

- This source provides an overview of naval history, including the African-led conquest of the Iberian Peninsula and the later Moorish influence on European naval strategies, as well as cultural exchanges through maritime routes.

- Kennedy, Hugh. (1996). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. Routledge.

- Kennedy’s work is a critical source for understanding the African-led Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula and the continuation of Roman-influenced administrative systems in Muslim-ruled Spain after the fall of the Roman Empire.

In-Text Citations

- For the role of Periplus ti Okun Erythraean in documenting African and Roman trade routes, Casson (1989) is a foundational text that provides primary information on sailing routes and trade opportunities along the African coast.

- Birley (1971) ati Ball (2016) provide extensive details on the life of Emperor Septimius Severus, his African ancestry, and the integration of African elites into the Roman political and military hierarchy.

- Mattingly (1995) ati Shaw (2014) offer context on the African provinces under Roman rule, detailing African military regiments and administrative structures like the Notitia Dignitatum, which recorded Roman military offices.

- For the Moorish-led conquest of the Iberian Peninsula post-Roman Empire, Kennedy (1996) ati Lewis & Runyan (1985) are key sources detailing the continuity of Roman cultural influences and the role of African rulers in shaping medieval Iberia.

4. The Early Interaction Between Europe and Africa Bibliography:

- Levtzion, Nehemia, & Hopkins, John F. P. (2000). Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History. Princeton University Press.

- This book compiles Arabic sources that document the history and trade of West African empires, such as Ghana and Mali, highlighting their involvement in the trans-Saharan trade network and the role of Islamic scholars in cities like Timbuktu.

- Curtin, Philip D. (1984). Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press.

- Curtin’s work provides an analysis of the networks connecting African empires to global trade routes, the influence of African middlemen, and the spread of religious and cultural ideas through these interactions.

- Hunwick, John O., & Boye, R. (2003). The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Rediscovering Africa’s Literary Culture. Thames & Hudson.

- This book examines Timbuktu’s role as a scholarly and cultural center in Africa, its rich manuscript heritage, and its influence on European perceptions of Africa’s wealth and intellectual achievements.

- Newitt, Malyn. (2005). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400–1668. Routledge.

- Newitt’s study covers Portuguese maritime exploration, the establishment of early trade monopolies in Africa, and the papal endorsements that sanctioned the Portuguese monopoly and the slave trade.

- Pakenham, Thomas. (1991). The Scramble for Africa: White Man’s Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912. Harper Perennial.

- While focused on the later colonial period, Pakenham’s work provides context on the European competition for African resources and the establishment of trading corporations that paved the way for imperial dominance.

- Hopkins, A. G. (1973). An Economic History of West Africa. Longman.

- This economic history examines the West African trade economy, the rise and fall of powerful empires like Mali and Songhai, and the transition from indigenous trade networks to European control.

- Daaku, Kwame Yeboah. (1970). Trade and Politics on the Gold Coast, 1600–1720: A Study of the African Reaction to European Trade. Clarendon Press.

- Daaku’s book provides an African perspective on the European entry into African trade, the establishment of forts, and the rise of trading companies like the Royal African Company.

- Thornton, John. (1998). Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press.

- Thornton explores the role of Africans in shaping the Atlantic trade, including African merchants’ responses to European traders and the development of joint-stock companies like the Royal African Company.

- Pope Nicholas V. (1452). Dum Diversas. Papal Bull.

- This historical document is one of the papal decrees that sanctioned the Portuguese right to enslave non-Christians in Africa and the newly explored lands, marking a crucial point in the history of the African slave trade.

- Rönnbäck, Klas, & Broberg, Oskar. (2019). Capital and Colonialism: The Return on British Investments in Africa 1869–1969. Palgrave Macmillan.

- This study traces the financial investments in Africa by European powers, focusing on how European nations profited from African resources and trade monopolies.

- Dunn, Richard S. (1972). Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624–1713. University of North Carolina Press.

- Dunn discusses the establishment of the joint-stock company model, tracing its role in financing the British empire’s ventures in Africa and the Americas, and the economic shifts that followed.

- Williams, Eric. (1944). Capitalism and Slavery. University of North Carolina Press.

- Williams’s classic work connects the rise of European capitalist enterprises, including joint-stock companies, with the African slave trade and explores how this system shaped global trade and wealth.

- Harms, Robert W. (2002). The Diligent: A Voyage through the Worlds of the Slave Trade. Basic Books.

- Harms provides insights into the economic, political, and social factors that drove the European slave trade in Africa, including the role of royal charters and trading corporations.

- Leo Wiener (1922). Africa and the Discovery of America. Vol. I–III

In-Text Citations

- For references on the trans-Saharan trade networks and the significance of West African cities like Timbuktu as intellectual centers, use Levtzion & Hopkins (2000) ati Hunwick & Boye (2003), which document the cultural and economic vibrancy of these trading hubs.

- Newitt (2005) ati Pope Nicholas V (1452) are key sources for understanding the Portuguese papal decrees and early European monopolies on African trade, which laid the groundwork for European exploitation.

- On the establishment of trading corporations like the Royal African Company and other joint-stock companies that bolstered European expansion in Africa, Thornton (1998), Daaku (1970), ati Williams (1944) provide foundational information.

- Rönnbäck & Broberg (2019) ati Pakenham (1991) offer broader insights into the economic motivations behind European rivalry for African resources, and Hopkins (1973) contextualizes Africa’s economic history in light of these external influences.

Terminology:

The terms B.C. ati C.E. are used to denote years in the Gregorian calendar system but differ in their origins and connotations. Here’s an explanation:

B.C. (Before Christ):

- Refers to the years before the estimated birth of Jesus Christ.

- It is a religious term rooted in Christian theology.

- Example: 500 B.C. means 500 years before the birth of Christ.

C.E. (Common Era):

- Refers to the same time period as A.D. (Anno Domini) but avoids explicitly religious connotations.

- C.E. is used in secular and interfaith contexts to promote inclusivity.

- Example: 500 C.E. means 500 years after the traditionally calculated birth of Christ.

Key Difference:

- B.C. is paired with A.D., which stands for “Anno Domini” (Latin for “in the year of our Lord”). These terms reflect a Christian-centric framework.

- C.E. ati B.C.E. (Before Common Era) are neutral alternatives to A.D. ati B.C., intended for a broader audience regardless of religious affiliation.

Both systems measure the same years and time periods; the difference lies in terminology and the cultural or religious neutrality of their usage.

Images:

- Olmec heads Mexico sunmọ 1500 ati 400 BC.

- A painting of the 12th orundun Song Dynasty.

- Malian Empire depicted on a map circa 12th century C.E.

- Fage, J. D., & Oliver, R. A. (Eds.). (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa: Volume 2, c. 500 BC–AD 1050. Cambridge University Press.

-

This is arguably the most comprehensive timeline summary I’ve encountered, detailing events leading up to, and following the Doctrine of Discovery.

It offers an in-depth and accurate depiction of historical developments, with bibliographic references and notes, which is very helpful for further scholarly, independent research.

Incorporating references significantly enhances its academic rigor; with valuable terms and references to guide further inquiry.

Brilliantly done!

-

This is jarring!

Considering the current shift in political ideologies, in the U.S, and Europe, with the normalisation of racist rhetoric, including sexist language, continued policies such as redlining, denialism, ‘othering’, under-funding, and warm nostalgia for the past, shouldn’t the Black community start developing ways to develop structures to protect itself from this attack?!

-

This is deep and extensive! I was never thought this history at school.

How can we change this narrative; particularly challenging mechanisms that perpetuate this hegemonic construct?!

-

@GenZTalks The perpetuation of Eurocentric and racially hegemonic systems, particularly those entrenched within the Black/White binary, is sustained through a variety of mechanisms, including silence, complicity, amplification, and adaptive survival strategies. These mechanisms, whether consciously done, or shaped through systemic constraints, implicate all social groups [both Black and White, aptly the peoples of African descent and Europeans] in maintaining the status quo. Achieving substantive and transformative change requires a critical awareness of these interconnected dynamics and a collective, intentional effort to dismantle the entrenched structures of racialized power that uphold them.

Changing the narrative and challenging the mechanisms that sustain Eurocentric and racially hegemonic structures require a multi-layered, intentional approach that addresses both systemic and cultural dimensions of power. Here are key strategies to consider:

1. Critical Education and Consciousness-Raising

- Decolonizing Curricula: Reform educational systems to include diverse, non-Eurocentric perspectives in history, philosophy, literature, and sciences. This ensures marginalized voices and epistemologies are legitimized and valued.

- Promoting Critical Pedagogy: Encourage critical thinking about power structures and their historical underpinnings. Paulo Freire’s concept of conscientização (critical consciousness) can guide individuals in recognizing their positionality within systems of oppression.

- Public Awareness Campaigns: Utilize media and art to challenge dominant narratives, amplify marginalized voices, and disrupt stereotypical representations.

2. Restructuring Institutional Practices

- Anti-Racist Policy Reform: Advocate for systemic changes in laws, governance, and institutional practices that perpetuate racial inequality. This includes addressing racial biases in policing, the judiciary, education, and healthcare.

- Equity-Based Leadership: Promote leadership models that prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion at all levels, ensuring marginalized communities have meaningful representation and influence in decision-making.

3. Disrupting Silence and Complicity

- Challenging Passive Acceptance: Create spaces where individuals can reflect on their roles in perpetuating hegemonic systems, whether through silence or complicity, and foster accountability.

- Encouraging Allyship: Equip individuals with the tools to act as allies, actively challenging racist ideologies, practices, and policies in their personal and professional lives.

4. Decentering Eurocentric Epistemologies

- Promoting Indigenous and Marginalized Knowledge Systems: Integrate indigenous, Afrocentric, and other marginalized frameworks into mainstream discourse, challenging the monopoly of Eurocentric paradigms.

- Critiquing Universalism: Expose how Eurocentric values often masquerade as universal, revealing their cultural specificity and inherent biases.

5. Fostering Intersectional Solidarity

- Intersectional Advocacy: Recognize that racial hegemony intersects with other forms of oppression, such as classism, sexism, and ableism. Advocate for coalitions that address multiple forms of marginalization simultaneously.

- Community-Led Movements: Empower grassroots movements that prioritize the voices of those most affected by systemic oppression, ensuring that solutions are informed by lived experience.

6. Challenging Survival Strategies and Internalized Narratives

- Empowering Marginalized Communities: Provide resources and platforms that allow individuals to reject survival strategies that conform to hegemonic expectations, fostering empowerment and resistance instead.

- Healing from Internalized Oppression: Support psychological and community-based interventions that address the impacts of internalized racism and colonialism, enabling individuals to envision alternative modes of existence.

7. Imagining New Futures

- Radical Reimagination: Develop counter-narratives and utopian visions that go beyond critiquing the status quo, envisioning equitable and inclusive societies free from hegemonic dominance.

- Cultural Innovation: Leverage art, literature, and media to construct and disseminate new symbols, stories, and paradigms that reflect diverse experiences and challenge ingrained power dynamics.

By addressing these interconnected layers, the narrative surrounding racial and Eurocentric hegemony can shift from one of acceptance and perpetuation to one of active resistance, accountability, and transformation. This process requires sustained effort, collaboration, and the courage to confront deeply entrenched systems of power.

-

@GenZTalks & @Nubian Why is this important – to write books that truly highlight the broader historical narratives of Africa’s vast and diverse histories, cultures, and contributions, which have often been marginalized or misrepresented in mainstream historical discourses?!

1. Counteracting Historical Erasure

African history has long been neglected or distorted by colonial narratives that portrayed the continent as a place without significant history or culture before European contact. Books on African history reclaim agency by documenting and analyzing Africa’s rich civilizations, such as Ancient Egypt, Mali, Great Zimbabwe, and Ethiopia, as well as its complex political, social, and economic systems. For those who feel disconnected, these works provide a means to rediscover suppressed or forgotten histories, filling gaps left by colonial-era education systems.

2. Promoting Self-Identification and Cultural Reconnection

For individuals of African descent, particularly in the diaspora, the historical displacement caused by slavery and colonization has severed connections to ancestral roots. African history books can serve as tools of cultural and intellectual reconnection, offering narratives that emphasize resilience, ingenuity, and creativity. This process is vital for fostering a sense of pride, identity, and belonging.

3. Critical Reflection on Colonial and Post-Colonial Impacts

Understanding African history is essential for critically examining the legacy of colonialism and its ongoing effects on the continent. By engaging with bibliographies that explore pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial periods, readers can contextualize current socio-political and economic challenges. This awareness helps dismantle simplistic or negative stereotypes and highlights the resilience and agency of African societies.

4. Diversifying Global Historical Perspectives

African history enriches global historiography by challenging Eurocentric perspectives that dominate academic and popular narratives. It emphasizes the interconnectedness of African societies with global phenomena such as trade, religion, science, and culture, demonstrating Africa’s integral role in world history. For readers unfamiliar with these contributions, such works broaden horizons and encourage more inclusive understandings of the past.

5. Educational and Advocacy Tools

These bibliographies are critical resources for educators, activists, and policymakers seeking to promote equity and justice. They help create curricula that accurately represent Africa’s contributions and struggles, fostering informed dialogue about issues like racism, development, and reparations.

6. Empowering Critical Thinking

Finally, African history books encourage critical thinking by engaging readers with diverse interpretations of historical events. They challenge myths and encourage questioning of biased sources, fostering a deeper appreciation of historical methodology and its impact on identity and power dynamics.

In conclusion, the importance of books and bibliographies on African history lies in their ability to reclaim suppressed narratives, foster identity and pride, provide critical tools for understanding contemporary issues, and challenge dominant historiographical paradigms. For those who feel lost or unaware, these works serve as guideposts to navigate not only Africa’s past but also the intricate web of global history and identity.

-

-

OnkọweAwọn ifiweranṣẹ

O gbọdọ wọle lati fesi si koko yii.