-

OnkọweAwọn ifiweranṣẹ

-

-

The Influence of

African American

Vernacular English

(AAVE) on Gen Z and

Alpha Slang:

Itankalẹ ti slang oni-nọmba nigbagbogbo pẹlu kikuru ati awọn ọrọ kukuru, bi kukuru ṣe pataki ni ibaraẹnisọrọ oni-nọmba.

Ìran Z, as a digitally native and socially aware cohort [born between the late 1990s and early 2010s] – has both adopted and adapted many features of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) in their everyday communication, leading to a notable shift in contemporary slang and reflecting broader cultural dynamics of appropriation, identity, and social influence.

Indeed, African American Vernacular English (AAVE), a linguistic variation traditionally spoken by African Americans, has played a significant role in shaping contemporary American English.

Despite its deep historical roots, AAVE has often been stigmatized, marginalized, and misunderstood by mainstream society.

While AAVE has been a feature of African American communities for centuries, its impact on mainstream culture has grown in recent decades, particularly through the influence of hip-hop culture, social media, and viral internet trends.

The Digital Age and the Rise of Gen-Z Slang:

Ìran Z, ati Gen Alpha have grown up in a digital landscape where information, trends, and culture are rapidly disseminated and consumed. Social media platforms like Twitter/X, TikTok, Instagram, ati Snapchat have become the primary avenues for social interaction, entertainment, and self-expression. Unlike previous generations, Gen-Zers ati Alphas are highly attuned to the cultural capital that can be gained from mastering and employing contemporary slang. Many of these slang terms, popularized and propagated through social media, have origins in AAVE.

For example, terms like “lit” (meaning exciting or excellent), “woke” (originally meaning conscious of social injustice), “clout” (referring to social influence or fame), “slay” (meaning to excel at something), “no cap” (meaning “no lie” or “seriously”), “rizz, or “rizzler”” (a term derived from “charisma, charm or appeal”), “gyaat,” a variation of “gyat damn” (an adaptation of “god damn”), “bussin’,” (an adjective meaning “amazing” or “excellent”), and “shade” (meaning to subtly insult someone) all have roots in AAVE and Hip Hop culture. These terms have been widely adopted by Gen-Z’s across racial and cultural lines, demonstrating the pervasive influence of AAVE on contemporary youth slang and culture.

Social Media and Digital Culture:

Social media platforms play a pivotal role in the dissemination and popularization of slang terms. On platforms like Twitter/X ati TikTok, short, catchy phrases or words often go viral, spreading quickly through shares, retweets, and trends. AAVE, with its rich, expressive, and often phonetically distinct lexicon, lends itself particularly well to these platforms. Words and phrases that originate in African American communities gain traction as they are picked up by influencers and celebrities with large followings.

For example, the term “no cap” (meaning “no lie” or “seriously”) became widely popularized after it was frequently used by hip-hop artists and subsequently adopted by TikTok users in various contexts. The rapid spread of “no cap” exemplifies how digital culture can amplify AAVE terms beyond their original communities.

Music and Pop Culture:

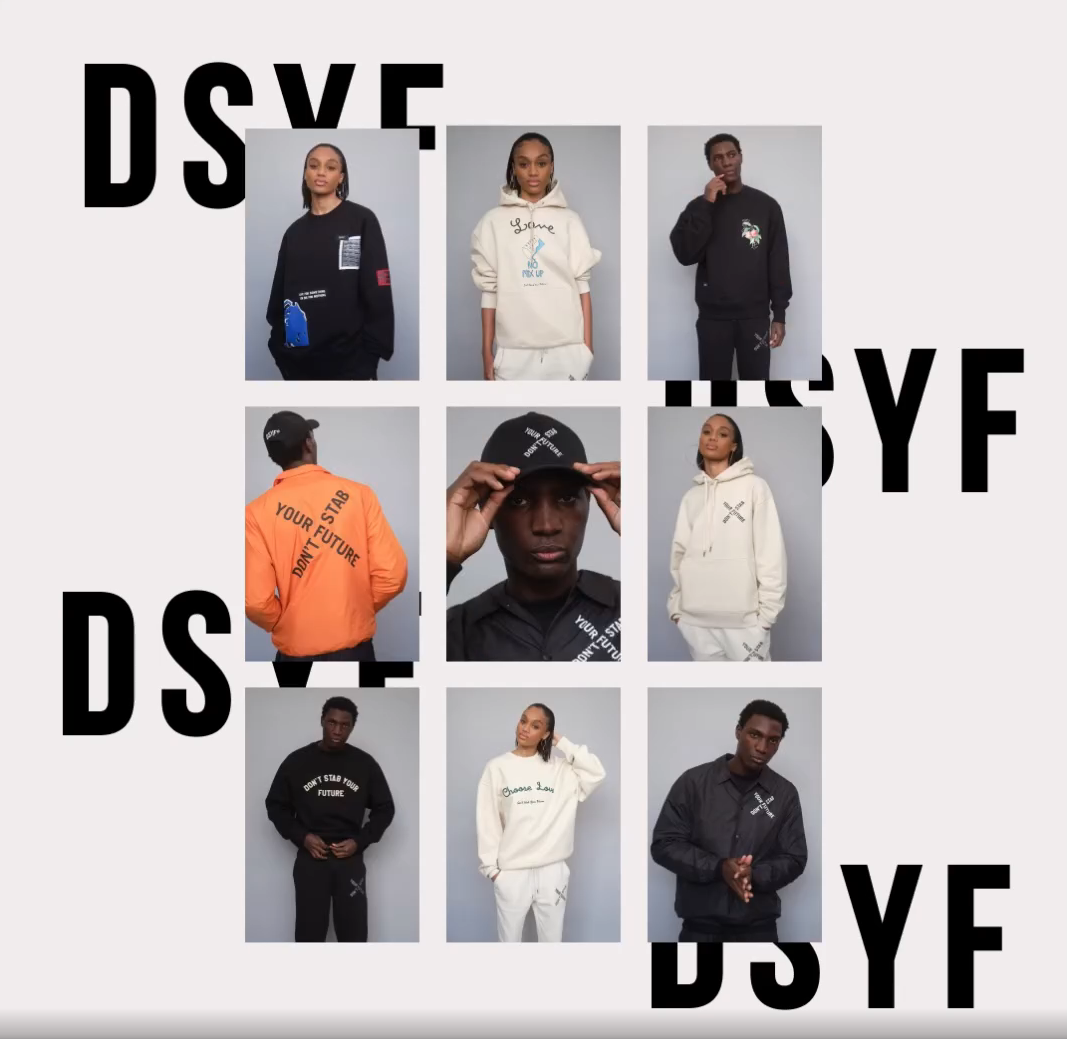

Hip-hop and rap music have been instrumental in bringing AAVE into the mainstream. As one of the most popular music genres among Gen-Zers, hip-hop’s use of AAVE in lyrics has significantly contributed to the adoption of these terms in everyday language. Lyrics from popular artists like Lil Wayne, Jay-Z, Snoop Dogg, Future, Cardi B, ati Megan Thee Stallion are often laden with AAVE, which, when repeated in songs, becomes part of the linguistic repertoire of young listeners. Furthermore, the culture surrounding these music genres, including fashion, attitudes, and language, is deeply interwoven with AAVE, making it a natural part of the vernacular for Gen-Z fans.

Cultural Appropriation and Linguistic Borrowing:

The use of AAVE by non-Black individuals raises important questions about cultural appropriation and linguistic borrowing. While the spread of AAVE terms can be seen as a form of cultural exchange, it often lacks the context and cultural significance these terms hold within African American communities. The widespread use of AAVE nipasẹ Gen-Z's ati Gen Alpha’s can sometimes result in the dilution of meaning or the perpetuation of stereotypes, as words are taken out of their original context and used without an understanding of their cultural significance.

This phenomenon has sparked debate over the ethics of using AAVE outside of its cultural context. On one hand, some argue that the adoption of AAVE by Gen-Z reflects a broader acceptance and appreciation of African American culture. On the other hand, critics contend that this usage can amount to a form of cultural appropriation, particularly when the same linguistic features are devalued when used by African Americans but celebrated when adopted by mainstream (often non-Black) culture.

The Social Implications of AAVE in Gen-Z Slang:

The incorporation of AAVE into Gen-Z slang reflects broader social and cultural dynamics at play. The acceptance and popularity of AAVE among Gen-Z can be seen as a sign of cultural respect and appreciation, signaling a shift in attitudes towards African American culture. However, it also highlights the complexities of linguistic identity and power dynamics. While AAVE is celebrated in mainstream culture when used by celebrities or influencers, its use by African Americans in professional or educational settings can still be stigmatized, reflecting a double standard that underlines broader issues of racial inequality.

Furthermore, the use of AAVE without a proper understanding of its cultural roots can contribute to the erasure of African American contributions to the linguistic landscape. It raises the question of whether the adoption of AAVE by non-Black Gen-Zers is an example of genuine cultural exchange or a continuation of a historical pattern of cultural appropriation.

Finally, the influence of AAVE on Gen-Z slang is a testament to the dynamic and evolving nature of language. As social media, music, and popular culture continue to drive linguistic innovation, AAVE remains a significant influence on contemporary slang. However, this linguistic borrowing is not without its complexities, raising important questions about cultural appropriation, identity, and the social implications of language use. As Gen-Z continues to shape the future of language, it is crucial to recognize and respect the cultural origins of the words and phrases that become part of our everyday speech.

Understanding the impact of AAVE on Gen-Z slang involves not only recognizing the linguistic trends but also engaging in critical conversations about cultural exchange, respect, and appropriation. As language continues to evolve, these discussions will remain central to understanding the broader cultural dynamics at play in our society.

-

@genztalks O ṣe awọn aaye to wulo.

Aṣa dudu ti ṣe alabapin pupọ si aṣa Gen-Z lọwọlọwọ, ati aṣa.

Fun ọpọlọpọ laarin agbegbe Black, AAVE kii ṣe ipilẹ awọn gbolohun ọrọ aṣa nikan. Nitootọ ilokulo le yọ awọn ofin kuro ninu itan ati itumọ aṣa wọn.J.

-

Ọrọ ti o gbooro ti isunmọ aṣa dipo riri nigbagbogbo da lori idi, oye, ati ọwọ ti MO le ṣafikun. Imọriri tootọ yoo kan riri awọn ipilẹṣẹ ti AAVE ati iwulo aṣa rẹ, dipo ṣiṣe itọju rẹ bi aṣa.

In contrast, appropriation happens when these terms are used for social capital without acknowledging or respecting the communities from which they originated.

Ultimately, it’s crucial for non-Black individuals who use AAVE to be mindful of the historical and cultural weight behind the language and to avoid contributing to the erasure or trivialization of Black culture.

-

Ko le gba diẹ sii @genztalks!

Nigbati awọn agbọrọsọ ti kii ṣe dudu lo AAVE laisi oye tabi bọwọ fun awọn ipilẹṣẹ rẹ, o le ja si itumọ aijinlẹ ti ede naa. O din kan ọlọrọ asa fọọmu ti ikosile to lasan slang.

-

-

OnkọweAwọn ifiweranṣẹ

O gbọdọ wọle lati fesi si koko yii.