-

AutorPublicaciones

-

-

Reconfiguring

Africa: A Critical

Black Philosophical

Analysis of the

Berlin Conference

of 1884-1885.

Introducción:

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, a gathering of European imperial powers, marked a turning point in the history of the African continent. Convened under the pretext of regulating European colonization and trade in Africa, the conference was, in reality, an exercise in violent expropriation, erasure, and subjugation. From a critical Black philosophical perspective, the conference represents the apotheosis of Eurocentrism, an embodiment of epistemic violence, and a negation of African sovereignty. The absence of African voices in decisions about their own lands exemplifies the deep-rooted racial hierarchy that underpinned the colonial project. This paper interrogates the conference’s implications, its ideological underpinnings, and its enduring legacy.

The Ideological Foundations of the Berlin Conference.

The Berlin Conference must be situated within the broader intellectual and political currents of the late 19th century. European imperial discourse was steeped in the logic of racial superiority, which posited Africans as incapable of self-governance. The conference was justified through the rhetoric of the ‘civilizing mission,’ an ideological framework that sought to rationalize the dispossession and brutalization of African societies under the guise of development.

Drawing from Frantz Fanon’s analysis of colonialism, we see how the European powers constructed Africa as a blank slate upon which Western civilization would be inscribed. The conference was not merely an act of territorial division but also an epistemological assault that denied African peoples the legitimacy of self-determination. This epistemicide—destruction of indigenous knowledge and political structures—was integral to the colonial enterprise.

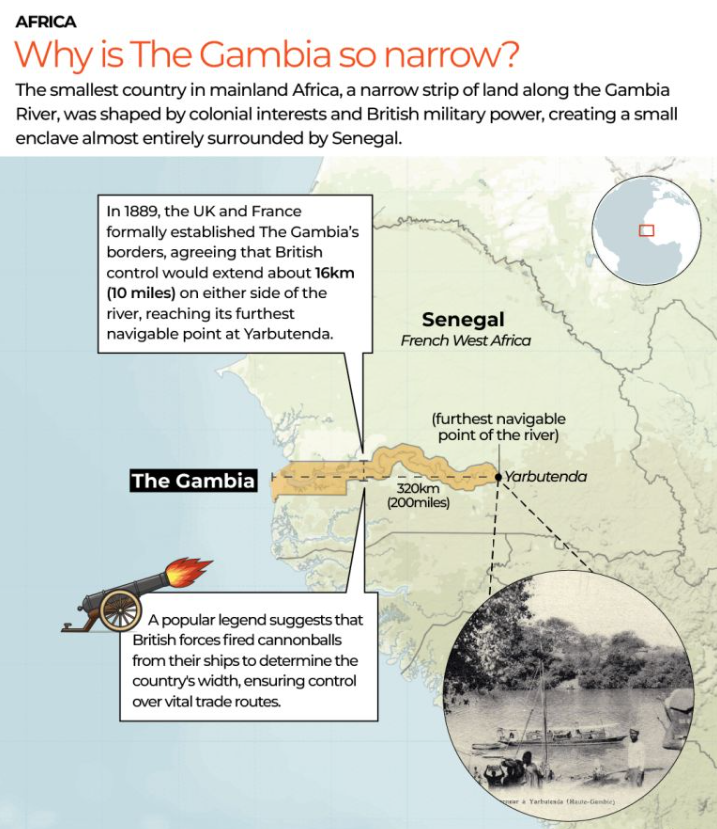

Have you ever looked at a map of Africa and wondered why its borders seem so unusual? With 55 countries, Africa has more nations than any other continent, yet its borders often defy natural landscapes and historical divisions. In some areas, they stretch in unnaturally straight lines, while in others, they zigzag through mountains, rivers, and even communities. But why is that? And what’s the story behind places like Bir Tawil — a land neither Egypt nor Sudan claims? Or The Gambia — a country so narrow it hugs the Gambia River, almost entirely surrounded by Senegal? Let’s explore the intriguing reasons behind these curious borders.

1: Bir Tawil – The Land Neither Egypt Nor Sudan Claims.

An illustrative example of the complexities surrounding Africa’s borders is Bir Tawil, a 2,000-square-kilometer (795-square-mile) stretch of uninhabited, arid land situated between Egypt and Sudan. In 1899, a colonial administration established a border along the 22nd parallel, separating the territories. However, a subsequent decision in 1902 reassigned the resource-rich Hala’ib Triangle to Sudan and Bir Tawil to Egypt for administrative convenience.

After gaining independence, both Egypt and Sudan adopted opposing views on the rightful boundary. Egypt argued in favor of the 1899 border, while Sudan maintained that the 1902 boundary was valid. Neither country has claimed Bir Tawil, as asserting sovereignty over it would require relinquishing claims to the more economically valuable Hala’ib Triangle. This dispute remains unresolved, demonstrating how colonial-era decisions continue to shape diplomatic relations and territorial claims in the region.

2: The Gambia – A Country Shaped by Colonial Convenience.

The Gambia, a narrow strip of land along the Gambia River, provides another example of the arbitrary nature of Africa’s borders. Nearly entirely surrounded by Senegal, The Gambia’s unusual shape reflects the economic motivations of colonial powers. Britain, seeking to control the vital Gambia River trade route, maintained a small yet strategically significant presence, while France controlled the surrounding regions. Rather than aligning with geographical or cultural considerations, the border was drawn to accommodate these competing colonial interests.

Today, The Gambia’s narrow and elongated form presents challenges for infrastructure development and regional integration. Limited access to surrounding territories and dependence on cross-border cooperation have complicated economic and political progress. This example highlights how borders established without regard for the realities of African communities continue to impact governance and development.

The Material Consequences: Dispossession and Subjugation.

The arbitrary boundaries drawn at the Berlin Conference disregarded the cultural, linguistic, and historical realities of African societies. As Walter Rodney has argued in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, European intervention transformed Africa into a mere appendage of Western capitalism. The continent’s resources, from palm oil to rubber, were extracted to fuel Europe’s industrial expansion, while African labor was dehumanized and exploited.

The conference did not merely partition land; it restructured African socio-economic systems to serve European interests. Traditional governance structures were undermined, indigenous economies were disrupted, and resistance was met with brutal force. The extractionist policies instituted during this period laid the foundation for neocolonial dependencies that persist to this day. The resultant economic stratification ensured that African states remained peripheral in the global capitalist order.

The Politics of Absence: African Silencing and Epistemic Violence.

One of the most egregious aspects of the Berlin Conference was the conspicuous absence of African representatives. This exclusion was not incidental but symptomatic of a broader Eurocentric worldview that denied African agency. The conference was predicated on the assumption that African voices were inconsequential to discussions about African land and futures.

Drawing from Sylvia Wynter’s critique of the coloniality of being, we understand this erasure as a fundamental aspect of modernity’s racial contract. Africans were positioned outside the realm of political subjectivity, reduced to objects of European control. The Berlin Conference was thus not just a diplomatic event but a manifestation of racialized ontology—an assertion that African existence was subordinated to European will.

The Legacy of the Berlin Conference: A Continuing Struggle.

The consequences of the Berlin Conference extend far beyond the 19th century. The artificial borders imposed by European powers have been a source of persistent conflict, from the ongoing Congo conflict, the Rwandan genocide to the Biafran War. These divisions, enforced through colonial rule, have perpetuated ethnic tensions and weakened pan-African solidarity.

Moreover, the extractive economic structures established during this period continue to shape Africa’s place in the global economy. The dominance of multinational corporations, the persistence of foreign debt, and the exploitative trade relationships between Africa and the West all stem from the economic arrangements formalized at the Berlin Conference.

Reclaiming African Sovereignty: Towards Decolonial Futures.

To move beyond the enduring legacy of the Berlin Conference, it is imperative to embrace a decolonial approach that prioritizes African epistemologies, governance structures, and economic self-determination. The project of decolonization must go beyond the formal independence achieved in the mid-20th century; it must seek to dismantle the colonial matrices of power that continue to constrain African development.

This involves reclaiming African history from Eurocentric narratives, investing in indigenous knowledge systems, and fostering regional integration to counter the divisive legacy of colonial borders. It also demands a re-evaluation of Africa’s role in the global economy, challenging the exploitative mechanisms of international trade and finance that maintain neocolonial dependencies.

Conclusion.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 was not merely a diplomatic gathering but a foundational moment in the systemic subjugation of Africa. It institutionalized the theft of African resources, the erasure of African voices, and the imposition of foreign domination. From a critical Black philosophical standpoint, the conference embodies the violent logics of racial capitalism and colonial modernity. The struggle against its enduring legacy is not merely a historical reckoning but a continuing fight for African sovereignty, dignity, and self-determination. The work of decolonization remains unfinished, and it is the responsibility of African nations and the global Black diaspora to dismantle the structures birthed in Berlin and to imagine futures beyond coloniality.

-

@africamonetary, Absolutely! The Berlin Conference represents one of the most egregious examples of epistemic violence, and was fundamentally about economic control, designed to legalize European plunder of African resources while preventing intra-European conflict.

This moment institutionalized racial capitalism, where Africa’s wealth—its land, minerals, and labor—was forcibly extracted for the benefit of European industrial expansion. African economies were violently reshaped to serve European markets, leading to the destruction of self-sustaining agricultural systems, the exploitation of labor (as seen in the forced labor systems of King Leopold II’s Congo), and the enduring underdevelopment of African nations.

The logic of colonial exploitation initiated at Berlin continues in modern neocolonial economic structures, where African resources remain disproportionately controlled by foreign interests – Congo, and South Africa for example.

-

Agreed! The arbitrary borders drawn during the Berlin Conference, without regard for ethnic, linguistic, or cultural considerations, have had lasting consequences on African political stability.

j

-

Many post-colonial conflicts across Africa – from North to South – can be traced to these imposed divisions.

This act of unilateral decision-making not only denied Africans the right to self-governance but also imposed foreign political structures that disrupted indigenous governance systems, cultures, and economic autonomy.

-

-

AutorPublicaciones

Debes iniciar sesión para responder a este tema.